Wind erosion involves the detachment, transportation, and redeposition of soil by wind, affecting crop and pasture productivity. Wind erosion can degrade land, infrastructure and dust particles can create air pollution. All soils are susceptible to wind erosion, which can be minimised by maintaining more than 50% ground cover to reduce wind-speed at ground level, and minimising soil disturbance. Where water erosion is also of concern, groundcover should exceed 70%. Wind erosion risk can be increased by some agronomic practices if not carried out as recommended.

WA soils and the impact of wind erosion

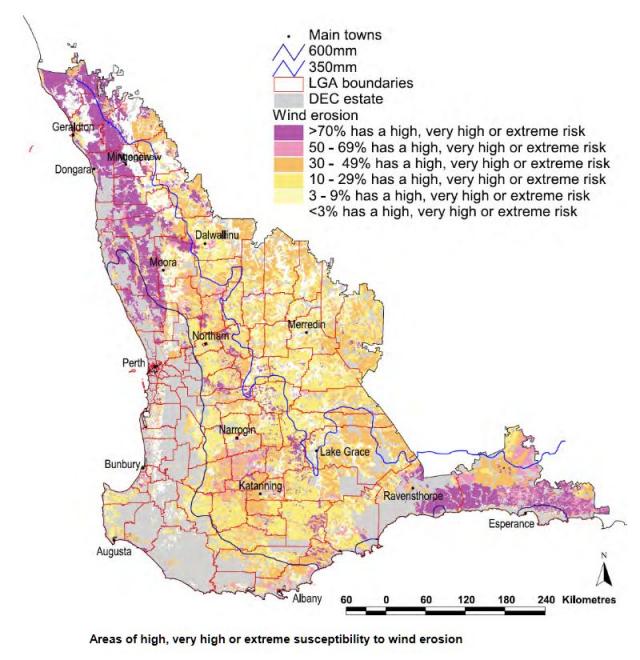

Western Australian soils generally have low inherent soil fertility and high susceptibility to wind erosion because of sandy surfaced soils. We have estimated that 6.4 million hectares (ha) of agricultural land in WA is at risk of wind erosion – 0.02 million ha at extreme risk, 0.9 million ha at very high risk and 5.5 million ha at high risk.

Management implications

- Current land use practices still result in some degree of wind erosion, with an estimated cost of $50–71 million per year.

- Climate variability and a drying climate will increase the risk of wind erosion in the current agricultural system.

- Increasing the use of stable ground cover (including living and dead vegetation and gravels) to prevent loss of soil, fine particles, nutrients and soil organic carbon is a practical and profitable option.

Minor wind erosion occurs every year to some extent in the agricultural areas of south west Western Australia. Severe wind erosion is more likely when large areas have poor ground cover, loose soil and are subjected to strong winds. A run of dry seasons increases the likelihood of poor ground cover, leaving soil more susceptible to wind erosion.

Have an early start to managing wind erosion

Some management decisions can be made well before any dry season. Climate forecasting for Western Australia is reasonably accurate, and by the middle of winter the information is good enough to allow planning for the spring to late-autumn period.

For properties with livestock, long term management could include:

- holding feed reserves for at least 6 months

- constructing a confined feeding area safe from erosion

- having sufficient water reserves and reticulated supplies for 6 to 12 months.

For cropping only properties, long-term management could include:

- matching machinery and design for controlled traffic farming (CTF)

- tree windbreaks

- claying sandy soils.

Managing wind erosion in cropping

Leave enough anchored stubble after harvest to provide protection from wind erosion until the following season. Following a dry season, there may not be enough stubble left after harvest to give protection until the next season. In that case:

- decide if harvesting is worth it (dollars and erosion risk)

- if harvesting, choose a harvest height and management to leave as much stubble on site as possible

- do not graze the stubbles and keep traffic to a minimum.

- See the photos on managing stubble levels to control wind erosion for more detail.

- Going to pasture, leave about 1,500 kilograms per hectare (kg/ha) of anchored stubble after harvest. This will leave about 1,000 kg/ha of anchored stubble by the beginning of autumn to give 50% cover during pasture establishment.

- Going to crop with full cut seeding, leave about 2,250 kg/ha of anchored stubble after harvest. This will leave about 1,500 kg/ha of anchored stubble by the beginning of autumn to give 50% cover during crop establishment.

- Going to crop with zero tillage, leave about 1,125 kg/ha of anchored stubble after harvest. This will leave about 750 kg/ha of anchored stubble by the beginning of autumn to give 50% cover during crop establishment.

- Going to pasture, leave about 1,000 kg/ha of anchored stubble after harvest.

- Going to crop with full cut seeding, leave about 1,500 kg/ha of anchored stubble after harvest.

- Going to crop with zero tillage, leave about 750 kg/ha of anchored stubble after harvest.

Assuming you have met the stubble targets at harvest:

- if grazing the paddock, remove livestock when stubble cover drops to about 50% or if any bare patches develop

- limit all vehicle movement in the paddock

- protect bare areas and high traffic areas

- if there are summer weeds, balance:

- the need to control them for the following crop

- the increased risk of wind erosion if control leaves bare ground.

This period is usually the highest risk (likelihood and impact) time of year for wind erosion: dry groundcover vegetation from annual crops and pastures is at its lowest level, prefrontal winds can be very strong at this time, and preparation for seeding and following operations tends to expose and detach soil.

Burning in windrows is preferred to blanket burning when wind erosion is the primary concern. However, there are sometimes good reasons for using blanket burning to reduce the amount of stubble, including where:

- tyned seeding machinery is not able to handle the high levels of accumulated stubble between windrows after 2 or more high-yield years; this is especially the case where barley has been grown in either of the previous 2 seasons

- frosted crop stubbles do not remain standing during seeding and can cause machinery blockages

- early sown canola crops need low stubble loads to get good establishment.

We recommend using controlled traffic farming (CTF) for minimum tillage systems to reduce soil disturbance and the area affected by soil compaction. Note: CTF where grade banks have been removed and tracks are up and down slopes increases the risk of water erosion.

Deep soil mixing and soil inversion using rotary spaders, large offset discs, mouldboard and one-way ploughs typically removes all soil cover and completely loosens the soil to the depth of operation. This has a very high risk of wind and water erosion, especially during and after dry seasons, when soil cover is low.

Use weather forecasts to choose safe periods for soil inversion, and plant into moist inverted soil as soon as possible after inversion to reduce the wind erosion risk.

What happens in the soil?

Many WA soils have a sandy surface with limited finer fractions. Wind erosion removes the finer fractions from the soil, which includes the clay, organic matter and soil nutrients. The loss of these particles reduces the water and nutrient holding capacity of the soil and hence soil fertility.

For every 3% of the nitrogen that is removed from the soil, there is a 2% loss in yield of the following crop. If the top 10mm of soil are subjected to winnowing by the wind, crop yields may be reduced by 25%.

Additional fertiliser applications will increase the soil fertility, but the soil may not return to its original productivity, because of the loss of smaller particles which retain most of the nutrients. Other on-site impacts include the deposition of sand on fence lines and in waterways and dams. This requires time and resources to remove.

Managing wind erosion in pastures

Perennial pastures can:

- reduce soil exposure by having more ground cover for more of the year, and generally have more upright elements to slow windspeed at soil level

- reduce soil erodibility by having binding root masses or runners than hold the soil in place.

This relative advantage of perennial pastures over annual pastures has been observed many times in periods of wind erosion.

All pastures should have at least a 50% anchored plant cover. This equates to about 750 kg/ha of dry residues needed at the break of season

Spring management:

- Use feed budgeting in late spring to calculate grazing pressures to stay above the target groundcover levels.

- Protect areas of heavy sheep traffic: laneways, watering points, sheep camps.

Summer management:

- Remove all livestock before groundcover drops to 50% or 750 kg/ha, or when erodible bare areas develop.

- Use confined feeding on low erosion risk areas.

Autumn and early winter management:

- Defer grazing of pastures during early pasture establishment.

- Plant windbreaks or shelterbelts around highly susceptible areas

- Where suitable, plant perennial pasture species, which have a stable base and rapid growth on early rains, to provide better protection from wind erosion

We recommend keeping at least 50% of the soil covered by stable crop or pasture residues. Stable groundcover reduces wind speed at the soil surface, physically covers the soil surface and captures any soil particles picked up by the wind. At least 30% of the groundcover needs to be anchored to prevent the rest of the groundcover from being blown downwind. With this level of groundcover, even loose soil will not move in most strong winds.

Wind erosion can still occur in small bare areas in otherwise well-covered paddocks, leading to severe blowouts. The most common hazard spots are sheep camps, previous erosion areas, gateways, around watering points and along fences or laneways. These areas need special protection, such as binding spray, clay, gravel, old hay or straw, to give a full cover.

Claying is a good option on very susceptible sands that also suffer from water repellence. However, claying is an expensive option when done at the higher rates and it has technical risks. We recommend you obtain advice from a professional or experienced operator before choosing this option.

Spread clay rich subsoil at about 75–100 tonnes per hectare to control wind erosion; higher rates are recommended to give the long-term benefits of reduced water repellence, improved water and nutrient holding capacity, improved pasture use and reduced risk from frosting in some circumstances.

Leave clay on the surface over the summer when the wind erosion risk is at its highest, and incorporate the clay into the top 5–10 cm before seeding. Incorporation is needed to prevent clay forming a surface crust that reduces seedling establishment and water infiltration.

Gravel can be spread at the same rates as clay spreading to get a stable surface. Gravel is preferred over clay on very susceptible and difficult areas, such as water trough aprons and at gates where livestock tend to congregate. Gravelled areas will drain well when it starts raining.

Chemical stabilisers (for example, hydromulch, DustBloc®, Dustex®, GluonTM) will give short-term dust control. These chemicals are expensive, at more than $1,000 per hectare. Dustex® and GluonTM require water at 1 litre per square metre (10,000 litres per hectare). Note that the crust they form is easily broken by any form of traffic.

Cultivation has the potential to increase erosion and is not recommended in sands. However, delving clays to overcome water repellence can lift large clods (greater than 2 cm in diameter) that protect the soil from erosion by reducing wind speeds at the soil surface. Delving requires experienced operators. Too much clay or the wrong type of clay brought to the surface can be detrimental to the following crops. Ploughing heavy soils (clay and loams) to bring up clods will stabilise eroding paddocks, particularly where the subsoil is moist.

Remove livestock and prevent them from returning to erodible paddocks. Livestock can be:

- put onto a well protected (not exposed to wind, good groundcover) paddock

- put into a confinement feeding area (stabilised surface, sheltered)

- agisted

- sold.

One sheep can detach hard-setting soil at a rate of 0.3 tonnes per week and sandier soil at a rate of up to 1 tonne per week. Over summer, this can loosen up to 60 t/ha on the heavier soils and 140 t/ha on sands. We recommend reducing or removing livestock on areas approaching the target groundcover. In this condition, livestock may have to be agisted, kept in feedlots or stable refuge areas or sold.

Feeding trails on paddocks with low levels of groundcover will increase the risk of soil erosion. We recommend confined paddock feeding and feedlotting in this situation.

Reduce vehicle traffic wherever possible. Vehicle traffic reduces groundcover and detaches soil.

We recommend using controlled traffic (tramline) farming for minimum tillage cropping systems to reduce soil disturbance and the area affected by soil compaction.

Any form of cultivation will increase the risk of wind erosion. Soil inversion (mouldboard ploughing is an example) can greatly increase the risk of wind erosion. Use weather forecasts to choose safe periods for soil inversion, and plant into wet, inverted soil as soon as possible after inversion to reduce the wind erosion risk.

Tree windbreaks are a durable and effective way to prevent erosion for highly erodible soils in areas exposed to highly erosive winds. This is good insurance for extreme years.

Tree windbreaks reduce erosive winds for 10–15 times the height of the windbreak when winds are at right angles to the windbreak. For a 10 m high, well designed windbreak, the erosion risk is minimal up to 150 m downwind. Wind speed gradually increases over the next 10–15 tree heights, at which point the wind speed returns to that upwind of the windbreak. Windbreaks also help to retain detached residues that may otherwise be blown away in strong winds.

Tree windbreaks will compete with crops and pastures for light, water and nutrients: design the windbreaks to minimise this.

Windbreaks are a long term capital commitment and we recommend you get good advice before designing and planting tree windbreaks.

Cultivating to bring clods to the surface, and scraping ditches and ridges, are used in some places to reduce windspeed right at the surface, and to trap moving soil particles.

In most cases we do not recommend this in Western Australia. Why? Because many of our agricultural soils are too sandy to produce stable clods, and the risk of summer storms and severe water erosion on cultivated soil is high.

We recommend that you get local advice about the risk before using this option.

Recovering from wind erosion

Reduce the potential for more erosion:

- remove livestock and prevent them from returning

- minimise vehicle traffic

- protect highly susceptible and valuable areas – gateways, laneways, yards, surrounds of houses and sheds – with binding spray, clay, gravel, old hay or straw to give a full cover

Encourage pasture recovery or establish cover crops to reach and maintain target groundcover. Soils that have been eroded are often more susceptible to wind erosion in the following summer.

Eroded paddocks usually recover slowly because erosion removes nutrients in the topsoil and the seed reserves of grasses. Paddocks in this condition are very susceptible to more erosion at the break of season.

In this situation:

- defer grazing until there is about 800 kg/ha of new pasture dry matter – this reduces the risk of wind erosion and increases pasture production for the season

- continue supplementary feeding of sheep in stable areas or confined feeding areas

- establish cover crops on the most eroded and susceptible areas (see cover crops section in Wind erosion control after fire) and graze to allow pasture species to develop.

Understanding seasonal risk factors

Wind erosion is a seasonal risk in the agricultural areas of the south west of Western Australia and results from several factors:

- The Mediterranean climate – cool, wet winters followed by a long, warm to hot, dry summer – has a relatively short growing season.

- Most agriculture in this area is based on annual crops and pastures – they dry-off in spring (September to November) and are harvested or eaten over summer (December to February), which reduces groundcover and loosens surface soil by autumn (March to May).

- There are often strong prefrontal winds (wind ahead of rain) in autumn, when groundcover is low and soil has been detached by livestock and vehicle movement or cultivation.

- There are extensive areas with sandy-surfaced soils – these are very erodible sands with low levels of clay. They have poor structure and are easily detached.

Resource condition target for wind erosion

Note that these targets and the likelihood ratings do not indicate actual wind erosion – they estimate the likelihood of erosion if erosive winds occur.

We have 6 ratings of erosion likelihood of a site, and group these as either 'acceptable' or 'unacceptable'.

|

Rating |

Physical characteristics |

Likelihood class |

|

Safe |

No wind erosion likely and ground surface unlikely to be affected. |

Acceptable |

|

Negligible |

Wind erosion unlikely although some minor dust is possible. Ground surface likely to remain intact. |

Acceptable |

|

Low |

Dust and minor soil movement is likely although ground surface will probably remain unchanged. |

Acceptable |

|

Moderate |

Dust and some sand movement and the start of ground surface particle sorting likely. |

Unacceptable |

|

High |

Widespread dust and soil movement and rippling of ground surface likely. |

Unacceptable |

|

Very high |

Widespread dust and sand movement and deep deflation (hollowing out) of soil surface likely. |

Unacceptable |

For the long term sustainability of the soil resource, we consider that less than 5% of the landscape should be in the unacceptable likelihood class each year, with the aspirational aim of less than 3% of the landscape being in an unacceptable likelihood class.

|

Target |

Hazard |

Criteria |

|

Above target |

Very low |

<1% of the landscape in an unacceptable likelihood class |

|

Above target |

Low |

1–3% of the landscape in an unacceptable likelihood class |

|

Above target |

Moderate |

3–5% of the landscape in an unacceptable likelihood class |

|

Below target |

High |

5–10% of the landscape in an unacceptable likelihood class |

|

Below target |

Very high |

>10% of the landscape in an unacceptable likelihood class |

Contact us

-

Justin LaycockFisheries and Agriculture Resource Management Research Scientist